In 2008 Elisa and her family bought a plot of land in Menlo Park and built a “smart” house—self- cooling, self-heating, with solar panels. The whole thing cost $450,000. Ten years later, with the start of Facebook’s fifty-six-acre expansion, the house has doubled in value. “It’s fantastic,” Elisa says.

At a recent community meeting, Elisa got a chance to ask a question of Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO. Referring to the local children of color, who don’t match the well-educated, interna- tional profile of Facebook’s employees, Elisa said,

“What about the young people, those who need jobs, from within this community?” Zuckerberg told her he planned to invest in the local schools and to make other contributions to the area. Elisa says she was satisfied. “As long as they stay conscious of not leaving out the little people from around here, then it will be okay. This,” she says, “can only be a win-win situation.”

Between them, Ravi and Gouthami have multiple degrees—in biotechnology, computer science, chemistry, and statistics. After studying in India and working in Wisconsin and Texas, they have landed here, in the international center of technology, where they work in the pharmaceutical-technology industry. They rent an apartment in Foster City and attend a Hindu temple in Sunnyvale, where immigrants from India have been building a community since the early 1990s.

Although the couple have worked hard to get here, and they make good money, they feel that a future in Silicon Valley eludes them—their one-bed- room apartment, for example, costs almost $3,000 a month. They could move somewhere less expen- sive, but, with the traffic, they’d spend hours each day commuting. They would like to stay, but they don’t feel confident that they can save, invest, start a family. They’re not sure what to do next.

After their nineteen-year-old daughter Stevie died by suicide in 2006, Melissa and Steve sought comfort by trying to help others. As volunteers with Kara, a grief support agency in Palo Alto, they’ve spent the past decade counseling parents of children as young as twelve who have taken their lives. When clusters of teen suicides emerged at two local high schools in 2009 and 2014, they were on hand to help.

“There is the implication of moral bankruptcy in Silicon Valley,” says Steve, “but I don’t think that’s the case. Parents have the best intentions. But they tend to think it’s a competitive world, so ‘I’ve got to teach my child to excel. If they excel, they’ll be able to compete. They’ll be equipped to cope and be happy.’”

Steve says that “the common denominator of people that commit suicide in this increasing phenomenon, particularly in the Bay Area, is that they are more sensitive than average.” He and Melissa describe children who take everything to heart, who don’t know yet what they think and feel, who need time and space to process their lives. Instead, these children find themselves falling off the treadmill that the culture has set them on.

“Our intelligence has surpassed our ability to express our emotions,” says Melissa. “We don’t learn about our feelings and how to express them. As a matter of fact, what we learn from a very young age is how not to express our feelings—how to keep ’em inside, how to hide ’em, how to get on with it. How to achieve.

“It’s hard to believe,” she says, “that we’re human underneath all this stuff that we see on the outside. We think, ‘We’re Silicon Valley: we’re the products of Silicon Valley, or the makers of Silicon Valley.’ And we’re really humans trying to survive under all of the facade that everyone sees.”

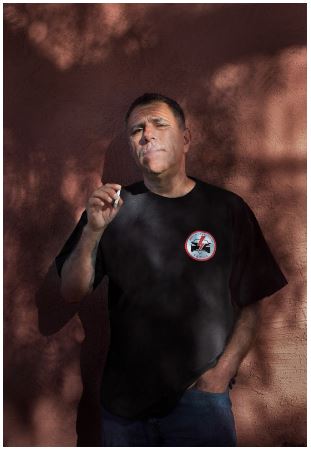

Cristobal is a United States Army veteran. He served for seven years, including three years in the war in Iraq. He now works full-time as a contract security officer at Facebook.

Beginning at sunrise, Cristobal stands at a crosswalk on Hacker Way, guiding the traffic— employee buses arriving, executives in company cars, pedestrians looking down at their phones who need to cross safely. He earns $21 per hour, which doesn’t afford him a home in Silicon Valley. So he lives in a shed in a backyard in Mountain View.

Cristobal has spent a lot of time thinking about his time in the army, about how he fought to defend the freedoms that allow a company like Facebook to flourish in this country. He has begun to organize with other service employees in the tech industry —cooks, custodians, security officers—to fight for better benefits, higher pay. He sees himself as part of an army of workers who are doing their best to support the big tech companies. But he doesn’t see any of the wealth trickling down to them.

Ariana remembers that it was sometime last spring when she’d returned home from school to find men placing “weird little metal contraptions” all over her apartment. They were using the instruments to test the air, her mother said, inside and out of the Sunnyvale apartment complex where Ariana lives with her family. The men found that the air was contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE) fumes.

TCE is a cancer-causing solvent. From the 1950s to the 1980s, when the electronics designed in Silicon Valley were still made there, local manu- facturers used it to clean silicon wafers before etching them with circuitry. Tons of TCE leaked into the ground. Now TCE had been found in the soil and the groundwater behind Ariana’s home, where a developer was planning to build a luxury apartment complex.

The men soon returned to install two filters in Ariana’s apartment: one in the living room and one in the bedroom that she shares with her younger brother. “At first I was kind of freaked out,” she says, to think that her family had been inhaling cancer- causing chemicals. And the filters themselves were kind of a nuisance: “They want us to run them on high all the time, but they’re really loud, so we don’t always have them on high. . . . I don’t know if the air filters are necessarily doing anything. I think part of it is them trying to give us peace of mind.”

Ariana says the men come back every few months to repeat the tests, but apart from that she doesn’t think much about the air anymore. She and her boyfriend, Elijah, are looking forward to finishing high school and moving away from the valley. They think Texas would be a nice place to live.

Teresa works full-time in a food truck. She prepares Mexican food geared toward a Silicon Valley clientele: hand-milled corn tortillas, vegan tamales, organic Swiss chard burritos. The truck travels up and down the valley, serving employees at Tesla headquarters, students at Stanford, shoppers at the Whole Foods in Cupertino. Teresa comes from Mexico. She lives in an apartment in Redwood City with her four daughters. On the door is a drawing in crayon that announces, “Bienvenidos Abuelos: Welcome, Grandparents.” In the last few weeks, Teresa’s parents have been visiting from Mexico. She hadn’t seen them since she was a teenager, twenty-two years ago. “Es muy dificil para uno,” she says. “It’s really hard.”

“It is amazing living here,” says Erfan, who came to Mountain View when her husband got a job as an engineer at Google, “but it’s not a place I want to spend my whole life. There are lots of opportunities for work, but it’s all about the technology, the speed for new technology, new ideas, new everything.

“We never had these opportunities back home, in Iran. I know that—I don’t want to complain. When I tell people I’m living in the Bay Area, they say, ‘You’re so lucky—it must be like heaven! You must be so rich.’

“We really pay too much for it all,” Erfan continues. “Not in physical costs, but in emotional costs. We are sometimes happy, but also very anxious, very stressed. You have to be worried if you lose your job, because the cost of living is very high, and it’s very competitive. It’s not that easy— come here, live in California, become a millionaire. It’s not that simple. The cost is too much.”

Richard has spent his entire adult life in the auto industry, loving his work and making good money. In 2010, the year that GM went bankrupt and the plant he worked at in Fremont closed, he was earning $120,000 a year. After Tesla took over the plant, Richard got a job on the manufacturing floor. He was paid $18 an hour, or less than $40,000 a year.

Richard started noticing things that didn’t seem right. As a line worker assembling car doors, he was required to work twelve-hour shifts, five or six days a week. Richard had a home, but he noticed young guys “who came in broke, with a bag of clothes” being hired, working the long shifts, sleeping in their cars, showering in the break room, and doing it again the next day. When a friend invited Richard to meet with the United Automobile Workers union, he agreed. Soon after that, when people complained to him about the low pay or long hours, he’d tell them that with the union, they could stand up for themselves. He handed out buttons and T-shirts, told people they had a choice. “We don’t want to break ’em,” he said of the company. “We just want a little larger piece of the pie—so we can have a cooler of beer every now and then, go camping once in a while.”

Though he’d never received a negative review, Richard was fired last October, along with more than four hundred other workers. The UAW has filed a complaint, alleging that Tesla fired workers who were trying to unionize. The worst part for Richard, he says, is that he hears the employees are now too scared to talk about the union. He believes that all his hard work has been in vain.

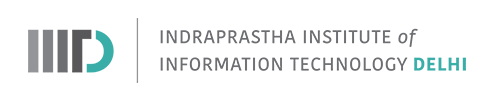

Mary Beth Meehan is a photographer, writer, and educator who uses images, text, exhibitions, and public installations to bring people together in the search for common ground. Her portraiture and community collaborations challenge dominant narratives across racial, cultural, and social boundaries, addressing often fraught public dialogue with powerful imagery, personal backstories and tender archival material that lend an essential layer of humanity, insight, and care. Originally trained as a photojournalist, Meehan reckons with the limits of photography and yet continually sees the potential of visual art to help us uncover our social conditioning and unlock a path to greater understanding.

Meehan’s work has been featured and reviewed in publications internationally, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Los Angeles Review of Books and Le Monde. Meehan has held artist residencies at Brown University, Stanford, the University of Missouri School of Journalism and the University of West Georgia. She has lectured and led workshops at the School of Visual Arts, New York, the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, in Boston, and the Missouri Photo Workshop. A native of Brockton, Massachusetts, Mary Beth received a Bachelor of Arts degree in English literature at Amherst College, and a Master of Arts degree in photojournalism at the University of Missouri, Columbia. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

Dr. Aasim Khan is Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Sciences and Humanities, IIIT-Delhi. Aasim is a political scientist with a specialization in global and South Asia studies. His research interests combine his academic training in political and social theory with a focus on information technologies and their entanglements with institutions of provincial, regional and global governance. Aasim holds a BSc (St Stephen’s College, Delhi University) and an MA from AJK Mass Communication Research Center (Jamia Millia Islamia). He also completed an MA from the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London) and then pursued his doctoral research at the India Institute, King's College London, UK. He was awarded a PhD in Politics and Public Policy in 2018. In 2022-2023, Aasim was awarded a Fulbright post-doctoral fellowship and was a Visiting Scholar in Political Science at the Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs, Brown University, USA.